I WILL RETURN again and again to that moment. I will keep a notebook in which I record the details. There will be poorly done sketches, graphs of time and motion, page after page on which I attempt to recover the past. I will pretend that memory is reliable, that it does not erode as quickly and completely as the brittle lines of an Etch-a-Sketch. I will tell myself that, buried somewhere in the intricate maze of my mind, there is a detail, a clue, some tiny lost thing that will lead me to Emma.

Later, they will want to know the exact moment I noticed she was missing. They will want to know whether I saw anyone unusual on the beach, whether I heard anything in the moments before or after she disappeared. They–the police, the reporters, her father–will ask the same questions again and again, staring into my eyes with desperation, as if by repetition they might make me remember, as if by force of will they can conjure clues where there are none.

This is what I tell them, this is what I know: I was walking on the beach with Emma. It was cold and very foggy. She let go of my hand. I stopped to photograph a seal pup, then glanced up toward the Great Highway. When I looked back, she was gone.

The only person to whom I will tell the entire story is my sister, Annabel. Only my sister will know I wasted ten seconds on a sand crab, five on a funeral procession. Only my sister will know I wanted Emma to see the dead seal, that in the moment before she disappeared, I was scheming to make her love me. For others, I will choose my words carefully, separating the important details from misleading trivialities. For them, I will present this version of the truth: there is a girl, her name is Emma, she is walking on the beach. I look away, seconds pass. When I look back she is gone.

This single moment unfolds like a flower in a series of time-lapse photographs, like an intricate maze. I stand at the labyrinth's center, unable to see which paths lead to dead ends, which one to the missing child. I know I must trust memory to lead me. I know I have one chance to get it right.

The first story I tell, the first clue I reveal, will determine the direction of the search. The wrong detail, the wrong clue, will inevitably lead to confusion, while the right clue leads to a beautiful child. Should I tell the police about the postman in the parking lot, the motorcycle, the man in the orange Chevelle, the yellow van? Or is it the seal that matters, the hearse, the retaining wall, the wave? How does one distinguish between the relevant and the extraneous? One slip in the narrative, one mistake in the selection of details, and everything disintegrates.

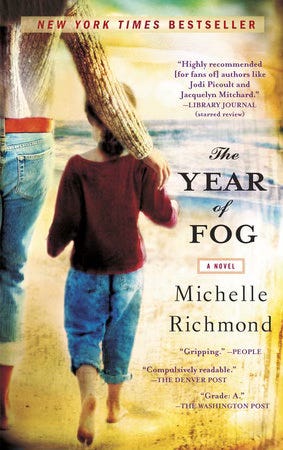

The passage above is excerpted from my 2007 novel, The Year of Fog. It’s hard to believe it has been seventeen years since that book was published! The book opens on Ocean Beach in San Francisco. In the opening paragraphs, a child disappears into the fog. When I wrote the book, we lived a few blocks from Ocean Beach. Now we live about twenty miles south. In the Bay Area’s mysterious microclimate, twenty miles can mean a difference of twenty to thirty degrees Fahrenheit.

Last week my mom was in town from Alabama, and we visited Land’s End. The ice plant was blooming, blanketing the hills over the Pacific in bright yellow. I walked into the small National Parks store perched above Sutro Baths with a view down Ocean Beach. The docent and I talked about the neighborhood—the things that are still there, the things that are gone, the things that have changed, the things that haven’t.

One of the biggest losses is Louis’ Diner (yes, that’s where the apostrophe always was in the big sign over the restaurant), where I often took my son to have pancakes before preschool or for a milkshake after school. Even after we moved away, it was a ritual to drive to Louis’ for lunch the day before spring break or summer vacation ended. It was a quirky little diner with a view that rivaled that of any restaurant in the world.

Nibs at 38th and Balboa, home of the best scone I’ve ever tasted, is also gone, replaced by a different bakery. (As you can see, I talk in superlatives when I mention my old neighborhood, but people really do come from all over the world to visit those few acres between the the Pacific Ocean and the Bay). The cafe Zephyr at the same intersection is also gone, replaced by a different, much busier bakery. Gus’s Bait and Tackle is still there. So is Simple Pleasures, which was a neighborhood hub when I lived there in the early 2000s and remains so today. As far as I can tell, they still roast their own coffee. The staff has changed, but the coffee is still great. During the pandemic, they added a parklet, so now there’s more outside seating for the increasingly sunny days of the Outer Richmond.

Balboa Movie Theater is still there too. It’s my favorite movie theater in the world. It survived during 2000s and 2010s while other beloved independent theaters in San Francisco shuttered. It survived the pandemic. Even though we live outside the city now, we still drive to the neighborhood several times a year just to see a movie at the Balboa and get dumplings at one of the many mom-and-pop dumpling shops along Balboa. I remember taking my son to the Balboa Theater three days in a row to see Ponyo many years ago. This summer, before heading off to college, he took his girlfriend to the Balboa to see Before Sunrise.

Yesterday, my husband met his old squad at Chino’s for burritos. It’s on the same block as Simple Pleasures, so you can grab a coffee to go after your burrito. Lucky me, he brought home a burrito for me too. It’s giant, so I had a quarter of it for dinner and will have the rest for lunch and dinner today.

If you live in San Francisco and forgot the Outer Richmond is there (easy to do if you live in other, busier parts of the city), do yourself a favor and head out to the avenues for a walk on the beach and some really good food. And if you visit San Francisco, set your GPS for Land’s End. It truly is one of the most beautiful places in the world. After you hike the gentle hill and get a glimpse of the Golden Gate Bridge, head up Balboa Avenue, where you’ll find dozens of wonderful little neighborhood restaurants and a magical movie theater.

If you just want to armchair travel, The Year of Fog is about the San Francisco I once knew. Although some establishments have come and gone, the landscape remains the same. And on summer days, you can still get lost in the fog.

Thank you for reading my author newsletter!