Not long ago I told my husband, “The book I want for Mother’s Day is You Could Make This Place Beautiful by Maggie Smith (not that Maggie Smith).”

He said, “We could make this place beautiful.”

I said, “We could, but first, more coffee…”

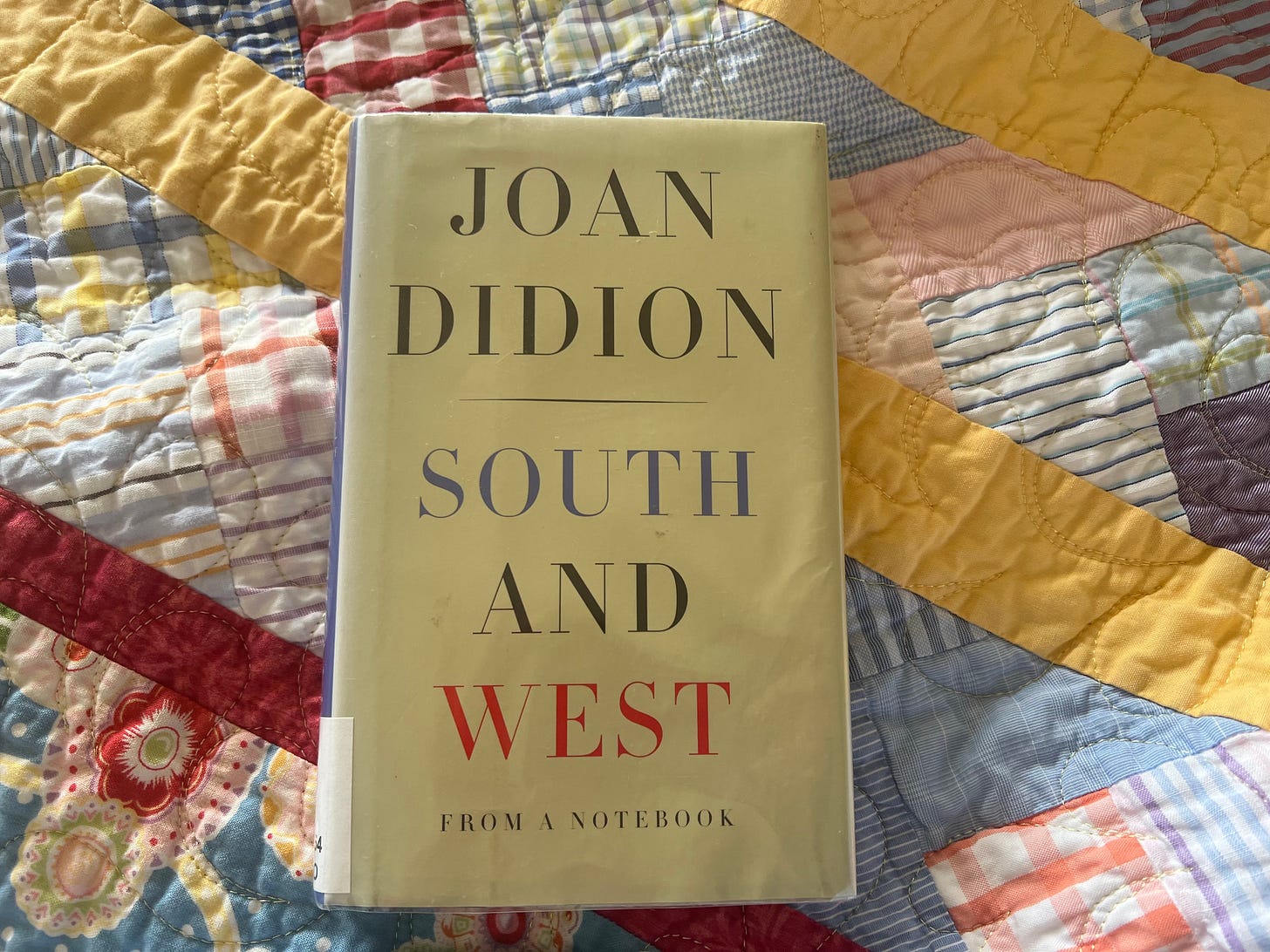

He said, “Would you put the Joan Didion book on the back of the couch?”

He meant: “If you were to set about making this place beautiful, would you leave the Joan Didion book open on the back of the couch, that most random of places, where you would be unlikely to find it the next time you went looking?” His meanings are precise, though his sentences—interrogative and otherwise—are vague. We have been married since the beginning of time, so I can pinpoint the heart of anything he says, diagram it right down to its marrow, no matter how much he leaves out.

He said the thing about the Joan Didion book because I had spent several minutes that morning wandering around aimlessly, coffee in hand, looking for the Joan Didion book, and he had finally asked, “What are you looking for?”

“That Joan Didion book I was reading yesterday,” I said.

He walked over to the back of the couch and said, “Could it be on the back of the couch?”

The question was rhetorical, obviously. He held the book aloft, spread open to page 87, exactly where and as I’d left it.

We have been married since the beginning of time, so I can pinpoint the heart of anything he says, diagram it right down to its marrow, no matter how much he leaves out.

What he meant was: you always put things where they don’t go, firm in your belief that you have put them in the exact natural place where you will later find them, and if I move them, you don’t like it, so for the sake of harmony, I leave books on the backs of couches and so forth.

Well, all of this is true, but still.

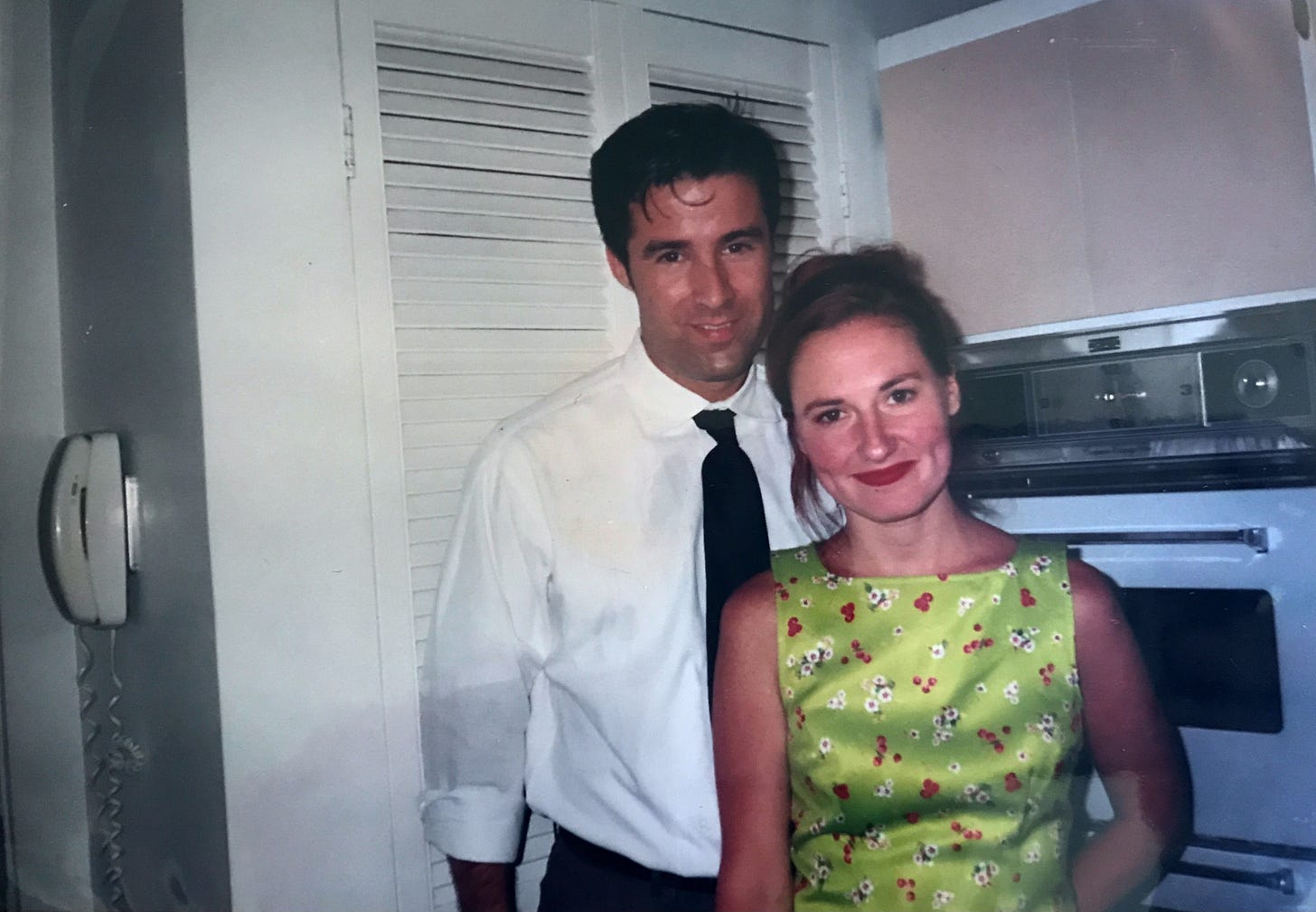

I refilled my coffee mug, the one he had taken down from the high shelf for me earlier that morning. The previous night, while unloading the dishwasher, he had put the mug up there where I could not reach it. This man sometimes forgets my low center of gravity, as if it has not been my continual state of being for the entire 27 years he has known me. When he handed me beautiful red mug that he purchased as a gift on a trip to the Baltics, I kissed him and said, “Thank you. I love this mug. It’s my favorite. Why do you put it so high up there?”

He said, “We can’t leave everything on the counter, all the time.”

It is true that in a marriage one individual may value accessibility, while the other may value clear and minimalist countertops. I can’t tell you the last time I found something I wanted without performing a minor excavation of the cupboards, high and low. Perhaps the secret to longevity in marriage is performing these acts of excavation with a sense of amusement and affection, as in, “Oh, we’re putting the Zyrtec behind the chocolate chips now, and the chocolate chips behind the salsa?” rather than irritation.

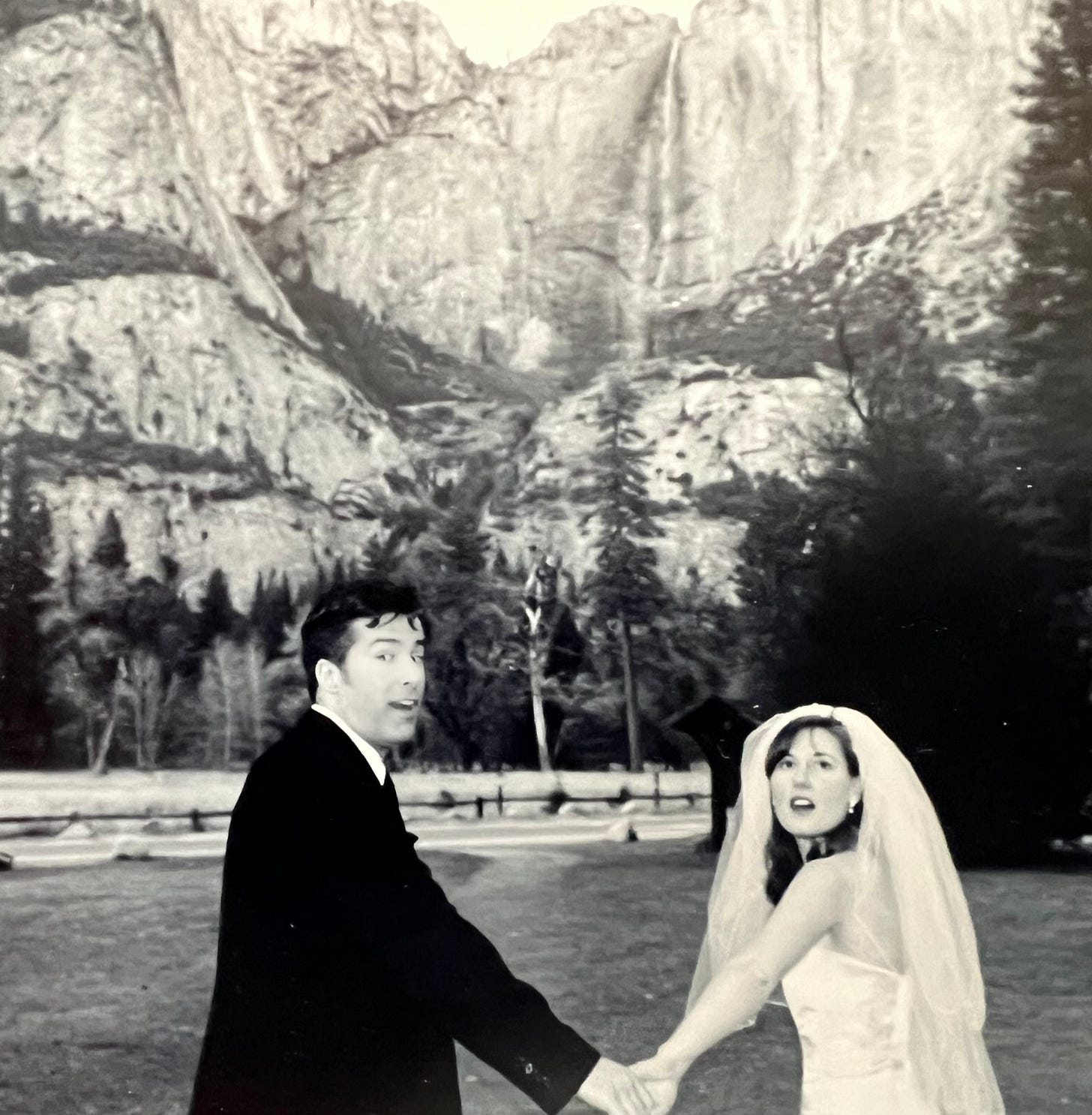

Many times each day, he is called upon to be amused rather than irritated by me. Many times each day, I am called upon to do the same. If you can master this single trick of the mind, marriage sweetens rather than sours on a fairly regular and cumulative basis. Of course, we have not always lived in the sweetening phase. A marriage of twenty-something years encompasses other moods and manners, many highs and lows.

“Marriage is memory, marriage is time,” Didion wrote in The Year of Magical Thinking. “Marriage is not only time: it is also, parodoxically, the denial of time.”

Notes on theme: I began writing this piece in my mind while I wandered around the house a couple of weeks ago, searching for the Joan Didion book. Over the years I’ve returned again and again to the subject of marriage, so my novel The Marriage Pact, in which two people try to hold their marriage together in the face of powerful outside forces, was a natural progression. Two of my earlier novels centered on a divorce: Dream of the Blue Room and Golden State. I don’t know when I began writing about the glue that holds a marriage together rather than the forces that tear it apart. For a while now, I’ve been working on the Paris essays—which are about Paris, of course, but also about love and its attending dangers.

In part 2 of this post, “Notes on a Birthplace by Way of Joan Didion,” we will travel Southward… Thank you for reading!

If you like this post you might enjoy my novel about a secretive and high-stakes marriage society—The Marriage Pact (“a smart, searing, frightening look at modern love” Today.com). And if you’re interested in the Pact’s rules for a happy, lasting marriage, visit The Marriage Pact on substack.

Michelle Richmond is the New York Times bestselling author of six novels and two story collections. She writes three newsletters: (on travel and writing), Novella with Michelle Richmond (the one you’re reading now), which features audio fiction and a serial novella, and The Caffeinated Writer (featuring articles and advice on writing and publishing.) She is the founder and publisher of

, which has been publishing flash fiction and memoir by emerging and established writers since 2005.